She is an artist, a writer and an advocate against Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) but before she becameall this, Ntailan Lolkoki had toovercome her childhood trauma and set her inner traumatized child free.

As a girl child in the Samburu community in Kenya, Ntailan lived an idyllic life. Her wake-up call was the mowing of cows and the chirping of birds nested in thicket bushes. Her evenings were beckoned by the setting sun, ushering in the return of the cows and the herdsmen.

Born to Maasai and Samburu parents, etched in her heart was a desire to go through the traditional rite of passage that introduced adolescent girls into womanhood. Female relatives’: aunties, grandmothers, elder sisters continually tell girls that a woman is not whole without FGM. The normalization of the practice makes young girls desire to go through it. She explains.

Ntailain says she narrowly escaped a traditional circumciser’s razor blade, after her parents split up. Her mother moved with her, and her other siblings to Ongata Rongai in Nairobi. But it is in an Ongata Rongai back-clinic that Ntailain would bleed at the hands of a quack surgeon’s blade. The procedure in the clinic was a far cry from the cultural celebration that her older sister had experienced. Ntailan secretly had longed for that.

“There is a lot of feast singing, dancing. The girls adorn their beads and traditional attires. Proud mothers ululate in jubilation. The transition from childhood to adulthood, a girl into a woman”. She narrates.

Her experience in the clinic in Ongata Rongai, though milder than infibulation and clitorectomy, she says traumatizes the victims and kills their ability to feel.

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes infibulation as the removal of the inner and outer labia, and the suturing of the vulva and categorizes it as a Type III female genital mutilation and a pharaonic circumcision in Africa. While clitorectomy as Type 1, is a non-medical removal of the clitoris performed during female genital mutilation (FGM). In medical application, it is sometimes used in cancer surgeries as a therapeutic procedure to remove sections to stop the spread of cancer.

(READ: Providing a Safe Haven for the “Desert Flowers”)

After her primary school, at Saint Mary’s, a Catholic boarding primary school in Maralal, her mother moved to Namanga on the Kenyan-Tanzanian border, deep into a Maasai village that she refers to as “the interior of the interior”. Her education would be cut short briefly as she stayed home to help her mother with daily chores but her father would come to her rescue and take her to school. The small triumph would later turn into a nightmare when at fourteen, she was raped by some man 17 years her senior. After that incident, she escaped and went to live with her sister.

She would much later meet an English man, to whom she got married and moved with to England. She was excited at the thought of leaving her past and starting a new life in Britain. Unbeknownst to her, the psychological and emotional wounds scourged deep into her being and it would take years of struggle before she finally confronted her pain and decided to do something about it.

The marriage did not last long, and she would pack her things and return to Kenya, where she turned to religion to numb her pain and to find meaning. By then her parents had passed on and her sister had turned to alcohol to deal with her trauma.

She says it was only after she met someone and fell in love that she profoundly started to deal with the trauma. Her moment of awakening had come during a church crusade, and she had from then on gone to work as a model scout and in social work.

In 2010, Ntailan would return to Europe. She came to Germany on a tourist visa working for a Christian counselling organization. She was later granted stay on grounds of searching for psychological support and healing of her trauma. She went through a reconstruction surgery in Berlin, but even then, it took small steps of courage to get to where she is today.

As a writer, she has already published her first book and working on the second one. “The writing started out of a desire to communicate freedom to others”. She says as part of her therapy, she started keeping a diary of daily accounts.

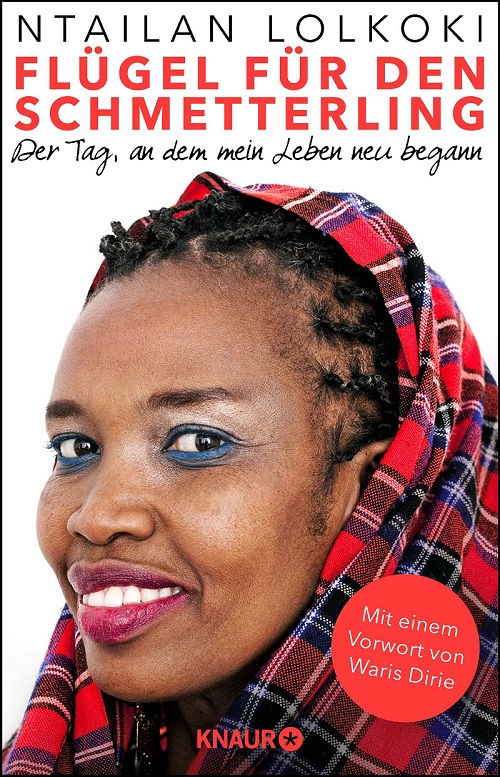

Her first book, “Wing for the Butterfly: The day my life started afresh” (Flügel für den Schmetterling: Der Tag, an dem mein Leben neu begann), details her journey, her childhood, teenage, marriage, sexual experience, the trauma that tagged along a larger part of her life and finally how she found herself.

At 49, Ntailan says she has finally discovered herself after years of being stuck in her childhood at age thirteen. She dedicates a large part of her life to the arts as an artist, actress, singer, song writer and author, all to encourage people undergoing trauma to talk about it and seek help. It is important to realise that people with an experience of trauma live in the prison of their own, because they bottle up the bad experiences and have no one to speak to.

She acknowledges efforts of other crusaders in the fight against FGM in Kenya and here in Europe. For instance, the work of Evelyn Brenda, Wari Dirie and Dr. Cornelia Strunz of the Berlin-Zehlendorf Desert Flower Hospital Center-Waldfriede. (READ: Kenyan Awarded the Louise-Schroeder-Medal in Berlin)

In her parting shot, Ntailan says “You are a human being and have the right to live a fulfilling life regardless of any trauma you have experienced. Take charge of your life and make something out of it, your past does not have to destroy your future”.