By Ann Brown

The Maasai people of Kenya and Tanzania, want royalties when their name is used. For instance, the Italian pen maker Delta introduced in 2003 the Maasai fountain pen as part of the company’s “Indigenous People” luxury line. The Maasai retailed for upwards of $600. “That’s like three or four good cows,” tribal leader ole Mbelati, 35, recently told a meeting of Maasai.

Ole Mbelati works for a Kenyan nongovernmental organization wants companies to stop profiting from the Maasai name, reports Bloomberg News. Ron Layton, a New Zealander who specializes in advising developing world organizations on copyrights, patents, and trademarks, tells the group that about 10,000 companies around the world use the Maasai name, selling everything from auto parts to hats to legal services. And about six companies have each made more than $100 million in annual sales during the last decade using the Maasai name. Among the the list of products bearing the Maasai name: Jaguar Land Rover sold limited-edition versions of its Freelander called Maasai and Maasai Mara in 2003; Louis Vuitton’s 2012 spring-summer men’s collection had scarves and shirts inspired by the Maasai shuka; and cushions by Diane von Furstenberg.

“Most of the value of the Maasai brand is not in the handicrafts the tribe produces,” Layton says. “It’s in the cultural value of an iconic brand.”

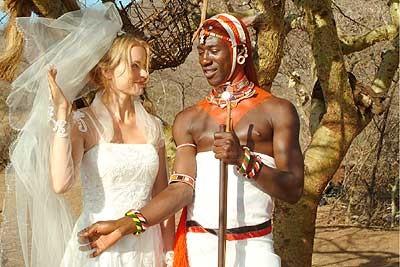

The Maasai, whose population is estimated at about three million, have held close to their traditions. They live in small mud-and-stick homes clustered around oval-shaped pens for cows and goats. The tribe is also an important tourist draw in East Africa. Ole Tialolo, Layton has spent the last four years working on the Maasai case, aided by a $1.25 million grant from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. They have created an organization to represent the Maasai, a Tanzanian nonprofit called the Maasai Intellectual Property Initiative. Ole Tialolo is working to persuade the traditional chiefs, elected officials, and heads of civic society groups to join MIPI’s general assembly.

“Legally, the claim is weak. The Maasai may be responsible for the creation of their culture, but they’ve never made an effort to enforce ownership of it, so they face an uphill battle doing so now,” reports Bloomberg.

But Layton argues, legal avenues are not the only option. He says the Maasai have a strong moral claim and the benefits for a company in associating with the Maasai would quickly fade if a half-dozen warriors protested at its headquarters and accused it of theft.

For the Maasai, a positive outcome of their campaign could mean a windfall. Then the challenge for the Maasai would be how to share the money and what to do with it. The plan now is that revenue from brand licensing will be channeled through MIPI to be allocated in Maasai districts for development work. Managing the money will be as vital as controlling the brand.

– Madame Noire