Spanish is not Jürgen Hass’s strong point. But he has his ice-breaker almost down to a T. “Estoy loco, soy alckolico y impotente,” (“I’m crazy, an alcoholic and impotent”) he scribbles on a piece of paper in dodgy Spanish. In the shantytowns of Paraguay, he says, it is the first line he uses when trying to convince women to let him father their children.

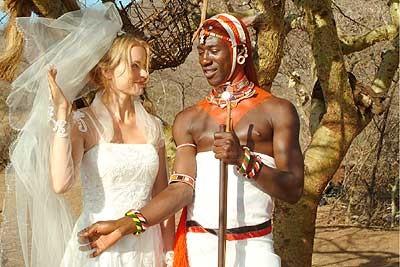

It works. Hass, 56, does not have sex with the women he meets, but he is now legally father to 350 boys and girls from three continents, and aiming to make it 1,000. Because he is German, the children he recognises automatically gain rights to child benefits and citizenship in his homeland. It is a form of social work, he says, a crusade to rescue youngsters from the developing world from poverty. The Paraguayan media have dubbed him “Superpapá”.

Not everyone sees Hass as a hero, however. He was jailed for fraud in Germany in the 1980s, and many of his countrymen claim he is simply trying to get his own back. In Paraguay, meanwhile, Hass is now a fugitive from justice, accused of flouting adoption laws. There is one thing that both Hass and his opponents can agree on, though: only jail or a change in the law will bring Superpapá down to earth.

That Hass is no ordinary eccentric becomes clear at his first meeting with the Guardian. Keen not to reveal his home address, “Señor Hass” has arranged a pick-up outside a supermarket on the outskirts of the Paraguayan capital, Asunción. To get there, our rickety taxi battles through a stream of multi-coloured 1950s buses, vomiting fumes out into the suffocating afternoon heat. A trail of car dealerships, pharmacies and evangelical churches runs along the roadside, occasionally punctured by green fields and country mansions. After 40 minutes, we arrive at the meeting point. A delivery truck packed with squawking chickens is the only thing waiting there.

We are, it seems, being watched. Within seconds, an ancient Mercedes Benz swings into view and a middle-aged German woman pokes her head through the window. “Press?” she asks, in heavily accented Spanish. Our ride, it appears, has arrived. Sporting three-day stubble, Hass is waiting in a nearby bar, surrounded by stacks of broken plastic chairs. On the table before him sits a bottle of Bavaria, the local beer, and a plate of manioc (cassava) and sausage. “I’m stranded here,” Hass says, explaining that the German embassy has confiscated his passport, though he either can’t or won’t say why. The embassy refuses to elaborate, though a spokesman does say, “We know him.” He adds wearily: “He’s been breaking our heads. He claims the German authorities are persecuting him. He’s a querulant [a sort of persistent quarreler].”

Back in Germany, prosecutors want to speak to Hass about allegations of deception. According to Lothar Liebig, a spokesman for the prosecutor’s office in the town of Frankental, Hass attempted to buy a flat at auction – even though he did not have the money to cover the purchase. “We are still investigating,” Liebig says. “These are simply accusations at the moment . . . It’s quite hard investigating someone who is in South America.” Hass denies any wrongdoing.

The Paraguayan police are after him too. After accusations by Teresa Martinez, a child protection officer in Asunción, that the German had violated adoption laws, a local judge put out an arrest warrant for Hass at the start of May. Martinez argues that it is a crime in Paraguay to lay claim to a child to whom you are not biologically related, something that Hass disputes.

Hass seems determined to shrug all this off. “Officially, I’m a fugitive,” he concedes. “But not really . . . I don’t live as an outlaw.” If that is the case, however, one wonders why meeting him is such a cloak-and-dagger operation.

Hass’s one-man war on officialdom goes back a long way. In the 1970s and 80s, he lived with his wife and two sons in Rees, a picturesque village beside the Rhine. He ran an insurance agency, but was also active in local politics, and became an MP for the centre-right Free Democrats. But in 1987 Hass was convicted of fraud and jailed for three years. The experience appears to have changed him from a small-time complainer to a full-blown tormenter of German officialdom. When he emerged from prison, his life collapsed. He lost his job, his wife left him, and he tried to kill himself. At the age of just 38 he took advantage of Germany’s generous pension system and took early retirement.

In the 90s, Hass began working as a legal adviser, despite having no formal qualifications. The state took a dim view of his activities, fining him about €100,000 (£68,000). Unable to pay, Hass spent several more spells behind bars. Germany, he says, has treated him “worse than a dog”.

“He’s a tragic figure,” says Peter Wismans, the deputy mayor of Rees. “For every brilliant idea that he had, at the rate of one a month, there were 10 completely eccentric ones with which he ruined his reputation.”

Six years ago, Hass began his transformation into Superpapá. His campaign to recognise as many impoverished children as possible began in Cologne, he says. “I saw this girl right in front of the Child Support Agency, sitting there crying,” he explains through a translator. “She was 13 years old and already a mother.” Because she was a prostitute, the girl was unable to name her baby’s father – which meant she was ineligible for child benefits. “So I said, ‘OK, I’ll assume fatherhood so you can get them.’ I didn’t want the child’s mother to lose out just because she couldn’t name the father. The only one to lose out would have been the child. So I lent myself to her.”

Hass has since recognised children in Romania, Ukraine, India, Moldova, Hungary and Russia. He first came to Paraguay in January 2005, on a two-week reconnaissance mission. In April, he returned with one destination in mind – the shantytowns of Asunción. “These are poor people, with no services, no light, no water, no money to buy medicine, no money for health care,” he says. “They can’t afford a proper [hospital] birth, and if you don’t pay for that, you don’t get to register the child,” he says.

With the aid of an interpreter – despite now having 30 Paraguayan children, Hass speaks barely a word of Spanish – he set out to work.

“If I see a pregnant woman I’ll approach her and say, ‘Do you need a father?’ I’ll tell her the advantages, about the German passport, the work possibilities,” he beams. Under existing German law, a man can register as a child’s father without proving he has had a relationship with the mother. The mother then becomes entitled to child support – and both she and the child gain the right to live in Germany.

Hass is not the only person to spot this loophole. One Berlin man has recognised 10 children from Bosnia and Vietnam, and between March 2003 and 2004 almost 1,700 women who were about to be thrown out of the country were allowed to stay after German men agreed to “father” their children.

Hass’s monthly pension of €1,000 (£680) is a small fortune in Paraguay, but he seems not to worry about being sued for maintenance by any of the mothers, since his “fatherhood” is purely a question of paperwork. “I’d lose my freedom [to continue recognising children] if I had to start taking care of these kids,” he says.

Hass now has close contacts with at least three nurses in an Asunción gynaecology clinic that is frequented by some of the city’s poorest women. “The hospital is very interested in my services,” he boasts. “It’s through me that they get paid.” Without his financial support, he says, most of these women would not be able to pay the clinic for prenatal treatment or even the deliveries.

The latest Paraguayan woman to “borrow” Hass is 26-year-old Liz Raquel Lugo Rojas from Lambare, a run-down municipality to the south-east of the capital.

“I’m super-happy,” says Liz when we meet near her two-bedroom home, which she shares with 11 relatives. She giggles excitedly at the thought of adding the name “Hass” to her children’s documents. There are three of them, and she must support them with occasional work as a cleaner, for which she earns around 10,000 guaranies (less than £1) a day. “He’s really my only hope,” says Rojas, who left school at the age of 12 and had her first child at 16. “It’s not so much for me that I’m doing this but for the children. I hardly went to school and they won’t for much longer [without Hass’s help]. The light has been switched on now, and there’s a ray of light in our darkness.”

Has she never worried why Hass might be offering this service? “No,” she says, “because I don’t believe someone would try to trick someone like me, knowing my suffering, knowing about all of my problems . . .”

As we talk, her sons Axel and Ulise, aged 10 and nine, and daughter Karina, four, hover curiously, shredding the napkins on our table into small pieces and constructing origami hats out of the remains. “The kids know what is going on,” says Rojas. Yet Axel – named after the Guns N’ Roses guitarist – seems unsure how he acquired his new German “papá”. Since Hass became a wanted man he has been unable to visit any of his 30 or so Paraguayan children. “There are police everywhere,” says the German woman who acts as his driver.

Father and son do not share a language: Axel speaks only Spanish and a sprinkling of Guarani, the country’s official language. Axel and Hass do, however, have a common interest in fast food. “I don’t have the money to do anything with them, but when Jürgen comes along they go to Burger King and eat hamburgers together,” says Axel’s mother.

Sitting in front of a large plate of chips, Axel grins knowingly and holds up a cartoon he has drawn of himself and his new father. Alongside a floppy-haired Hass, Axel has sketched himself with a speech bubble bursting from his mouth. “Papá,” he has written inside.

Much has been made of Superpapá’s supposed desire to get even with Germany. His surname even means “hatred” in German. Yet he does not come across as an angry man. “It’s a lovely play on words,” he says, “but it’s not true. I don’t just want to damage Germany. I am actually willing to do something good for Germany.”

His goal, he claims, is to break down national borders. “I’m willing to make a contribution to peace – and the only way to do that is by having a mixture of races and by speaking other languages. I want to help not just Germany but Europe as a whole,” he says as a three-legged mongrel totters by towards the bar’s foul toilet.

Despite the continued arrival of large bottles of Bavaria, Hass exudes an air of calm certainty. His ideas, however, become increasingly implausible as he describes his “activities” as a step to revolutionise both German and European politics. “I am a very dangerous man for the German Republic,” he claims. “Just imagine if I had 5,000 recognised children in the whole world. With their mothers, that would be 10,000 people. If they all came to Germany I could form a city of 50,000 people” – he doesn’t explain where this figure comes from – “who would all vote for me if I went for the Bundestag.”

So this is the future of politics?

“Si!” he cheers.

“I very like Guinness,” he adds in broken English. “Maybe now I’ll appear in the Guinness [World Records].”

Hass claims there are 50 more German expats who are either recognising fatherless child- ren in Paraguay as part of his campaign, or plan to do so in the near future. It seems an implausible figure, but Hass does introduce Werner Stassek, a twice-married 67-year-old from Berlin, who has lived in Paraguay for 24 years. “I’m willing to do this,” Stassek agrees in a German bar on the outskirts of Asunción, where a picture of Kaiser Wilhelm II hangs above the fireplace.

“It’s part of a revenge campaign, yes. But Hass is deeply committed to the children and wants to help them in the best way he can.

“The German state is not very happy,” Stassek concedes, with a cheeky laugh. “Anyone can acknowledge 1,000 children. At the moment they can only try to limit the damage but they cannot stop German citizens from asserting their paternity.”

This is true – but not for much longer. In April, Germany’s justice minister, Brigitte Zypries, announced that she wanted to change the law, giving the state an opportunity to appeal against “dubious fatherhood” cases. Although Hass was not the only reason for the change, he appears to have a lot to do with it. “We know who he is,” a spokeswoman for the justice ministry admitted.

But Stassek, like Hass, does not seem to be taking the campaign as seriously as he might. Every few minutes our conversation veers off into increasingly bizarre joke-telling sessions. “There’s this man and he goes to a pharmacy,” cuts in Stassek at one point, “and asks for some arsenic. But the employee says, ‘You need a prescription for that, you know.’ So I say to him, ‘Well, my friend, I haven’t got a prescription . . .'” He splutters into his coffee, in anticipation of the punchline. “‘But I have got a picture of my wife.'”

The last meeting with Superpapá is to take place in a landfill site. Hass is hiding nearby, and his driver is jumpy as she makes the final arrangements. “There are too many police around,” she mutters furiously as if we were responsible for leading them to Hass’s hideout. “You have to understand the risks we are running,” she says.

In fact, the Paraguayan photographer assures her, the large police presence is down to the country’s president, who is travelling to the interior on official business. It comes as little comfort to Hass’s own mini-entourage, however. “It is too dangerous for you to meet with Hass,” the driver insists. “We are scared.”

Eventually, she tells us to wait, halfway down a mud track. After more than half an hour, the beige Mercedes pulls into view again and Hass gets out. “How long will this take?” his minder babbles. “It must be quick.”

Hass himself seems less concerned as he poses for photographs just behind the rubbish tip. He grins into the camera, and waves around his blue petrol attendant’s cap as if he is rather enjoying his new-found celebrity. “You must tell everyone,” his friend whispers into my ear, “that he is doing this all for the children.”

“Next is India,” Hass says cheerily, motioning violently upwards with his right arm. “My aims are as high as the sky”