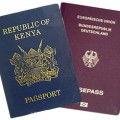

The Bible tells us that “no one can serve two masters”. This is a sentence that staunch opponents of dual citizenship in Germany’s conservative “Union parties” (CDU and CSU) love to quote in the context of the debate on dual citizenship. It is not a good argument for a number of reasons. Firstly, a citizen of a democratic state is not a servant. Secondly, everyone knows that people who have two jobs are not torn apart by the fact that they have two bosses.

Quite apart from that, the sentence they quote means something entirely different, namely that one cannot serve God and Mammon at the same time. It is about not being stingy. This is what makes it all the more incomprehensible that members of the Union parties are once again demonstrating such stinginess when it comes to discussing citizenship in their coalition negotiations with the Social Democrats and still acting as if having two citizenships simultaneously is a fundamental evil.

The resistance to dual citizenship is the last battle in a war that has been waged for decades under the banner “Germany is not a land of immigration”. This war was an assault on appearances because everyday life in Germany shows that we are living in a society of immigration. Recognition of dual citizenship means recognition of this fact.

The obscure “option model” from 1999

Dual citizenship means that citizens who are at home in two cultures are no longer required to tear themselves in two. It takes citizens the way they are: with their backgrounds, their traditions, their roots and the identity that results from all this.

Certainly, new citizens have to decide, but not whether they now feel a little more Turkish or a little more German; they have to decide in favour of democracy, a state governed by the rule of law and the basic principles on which the constitution is built. Dual citizenship can be a help in this respect.

EU citizens, ethnic Germans who have resettled in Germany after 1993 and the children of dual-nationality marriages are getting along just fine in Germany with dual citizenship; why should it be any different for German-Turks? One cannot decide on the basis of origin whether a person may have one passport or two.

The 1999 reform introduced the obscure “option model” that obliges people to choose: children born to foreign parents in Germany are initially granted two citizenships, but have to decide in favour of either German citizenship or the citizenship of their parents by the time they are 23.

Even when it was introduced in 1999, this model wasn’t the wisest of solutions; it was a stopgap measure taken by the coalition of Social Democrats and Greens in order to ensure a majority for at least a minor reform in the wake of the outright opposition of the conservatives who had recently won the state parliamentary election in the state of Hesse. Since then, what was expected at the time has now come to pass: the “option model” is damaging integration and causing legal uncertainty.

The Expert Council on Integration has now made a proposal that the Union parties would do well to accept: dual citizenship should be granted to the transition generation. That would be a wise compromise. And surely Angela Merkel can have nothing against wisdom.

Heribert Prantl

© Süddeutsche Zeitung / Qantara.de 2013

Prof. Dr. Heribert Prantl is a member of the senior editorial team at the German daily newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and editor in chief of the paper’s domestic policy section.

Translated from the German by Aingeal Flanagan