In 1969 at only 22 years old, Abdilatif Abdalla a renowned Kenyan poet and political activist was incarcerated at Kamiti Maximum Prison for his critical views published in the pamphlet- Kenya Twendapi? (Kenya, where are we heading to?). His crime was portraying the dismal performance of post-colonial Kenya and politics that went against the objectives of independence.

In the pamphlet, Abdalla called for political resistance to the regime. What he now terms, “its dictatorial tendencies and politicians who seemed more interested in amassing wealth, rather than serving Kenyans”.

After being arraigned in court, Abdalla was convicted of circulating material against Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta’s KANU government. A risky time for political activists in Kenya, who were arrested through the period leading to Kenya’s second President, Daniel Arap Moi’s regime.

Now a retired Professor, Abdalla was born on the 14th of April, 1946 in Kuze, the Old Town part of Mombasa, as a third born in a family of five. He started school at the Faza Primary school near Lamu before he moved to Takaungu, where he lived with his great uncle Ahmad Basheikh, who was a school teacher and also a poet. May be where he formed his interest in poetry.

His gaining impetus in the world of Swahili poetry and literature did not come easy.

At only 22 years old, Abdalla was incarcerated at Kamiti Maximum Prison for his critical views published in the pamphlet- Kenya Twendapi? (Kenya, where are we heading to?). In the pamphlet, Abdalla called for political resistance to the regime.

While in prison, he befriended a prison warden whose benevolence saw him smuggle a pencil to the captive Abdalla. He started writing poetry on sheets of toilet paper, which he says in those days, was rough and substituted writing pads.

It’s during this time in seclusion in prison, that he penned his first poem ‘Nshishiyelo ni Lilo! ( ‘I Hold Fast to What I Believe In’), an epic narration of poetic emotions expressing his frustration but resonating a determination to forge forward with his convictions. It was a poignant message directed to his brother and mentor Sheikh Abdilahi Nassir.

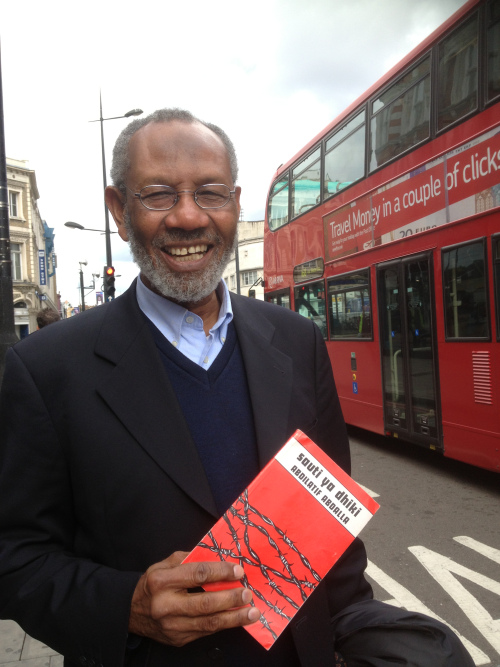

It was those poems written in prison and smuggled to his elder brother Sheikh Abdilahi Nassir for publication that pushed him to fame. Among the poems written during the three years of solitary confinement, were published in 1973 in his anthology called Sauti ya Dhiki (Voice of Agony).

His collection of poems written in prison won the 1974 Jomo Kenyatta Award for Literature, ironically carrying the name of the man who incarcerated him.

Abdalla points out, the poetic messages sometimes appear unpalatable to contesting ears but are crucial in addressing ills that bedevil the society.

In his work, he uses poetry as a medium for political activism. His poems interlink with other genres of creative and academic writing, and include aspects of politics, language, history and lyrical narrations. He has been an ardent contributor to the East African literary scene.

His brother was instrumental in building his political interests. It was through the books and material he gave him that Abdalla became politically aware of political happenings in post-colonial Kenya, Africa and the world at large.

Abdalla says he was determined to bring positive change in the political narrative of the time, despite the fact that civil and political rights of newly independent countries like Kenya were curtailed for fear of upheavals or political disobedience.

After his release in 1972, Abdalla lived in exile in Tanzania and worked at the University of Dar es Salaam’s Institute of Kiswahili Research until 1979. He would later get a job with the British Broadcasting Corporation’s (BBC) Swahili Department in London, where he worked until 1986.

He later worked as Editor-in-Chief of the current affairs monthly magazine Africa Events, published in London. He moved to teach Kiswahili at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, till 1995. He then left for Germany, where he had been offered a position as a Lecturer for Kiswahili Language and Literature at Leipzig University, where he taught till 2011, when he retired.

The linguistic and cultural differences in Britain and Germany presented a hurdle for his writing, but this did not deter his determination to write. While living in London he wrote a few poems in English, which was not his specialized language of communication.

He says Swahili poetry gives deep meaning to messages that address social and political problems, as well as communicates to populations with low literacy levels.

“Messages from the poetic genre are effective if communicated to an audience through oral narrations”, he quips.

This conviction is why he insists that poetry has to be delivered as an oral narration rather than on paper. “Poetry on paper is dead”, he says.

His poetry illustrates changes that the Swahili language has undergone from a cultural medium, to a linguistic emblem that carries similarities among Swahili speaking people especially those found at the coast of Kenya and in Tanzania. He writes in a style that incorporates both the classic and modern Swahili diction but remains relevant to people of all walks of life.

Some of his publications include ‘Utenzi wa Maisha ya Adamu na Hawaa’ (an epic poem on the life of Adam and Eve), (Ed.), ‘Utenzi wa Fumo Liyongo by Muhammad Kijumwa’, ‘Introduction to T.S.Y. Sengo’s Shaaban Robert: Uhakiki wa Maandishi Yake’, ‘Wema Hawajazaliwa’ (a Kiswahili translation of Ayi Kwei Armah’s novel, The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born, among others.

Abdalla says he found meaning while teaching African Literal studies in London and Leipzig Universities, where he inspired his students to recognize the significant connection between literature and politics.

He adds that young people particularly, Kenyan youth are in dire need for mentorship, to be dependable future decision makers in socio-political set-ups.

Since his retirement from active academic work in 2011, Abdalla enjoys spending time with his family and travelling extensively speaking on poetry, African literature and politics.

More sentimentally, as a proud father and grandfather he cherishes connecting with his family of 7 grown up children and 14 grandchildren, based in London and Hamburg.