On a Sunday afternoon, eight Kenyan women chat in a small apartment. Bongo flava, the Tanzanian hip-hop music popular among Kenyans, blares from two column speakers in the room.

The women are in Kypseli, a neighborhood north of Athens city center marked by closely spaced old apartment blocks. Its narrow streets are overtaken by cars. Some walls are sprayed with graffiti. About 15 percent of the apartments in the neighborhood are vacant, and another 15 percent are occupied by migrants.

But for these women, the neighborhood represents their success. Their gathering is their monthly chama, or merry-go-round meeting, in which they each contribute 200 euros ($216) and one of them takes home the total. This is a common money-saving practice among Kenyan women. Most of them send the money back to Kenya to pay for their children’s school fees and other needs.

These women feel privileged. They work as domestic staff in affluent Athens suburbs, earning between 600 and 1,000 euros ($648 to $1,080) per month. In Kenya, the monthly salary for housemaids and children’s nannies ranges from 5,844 shillings to 10,954 shillings ($57 to $107), depending on location. And even by the standards of Greece, where the monthly minimum wage is about $684, the women are doing OK.

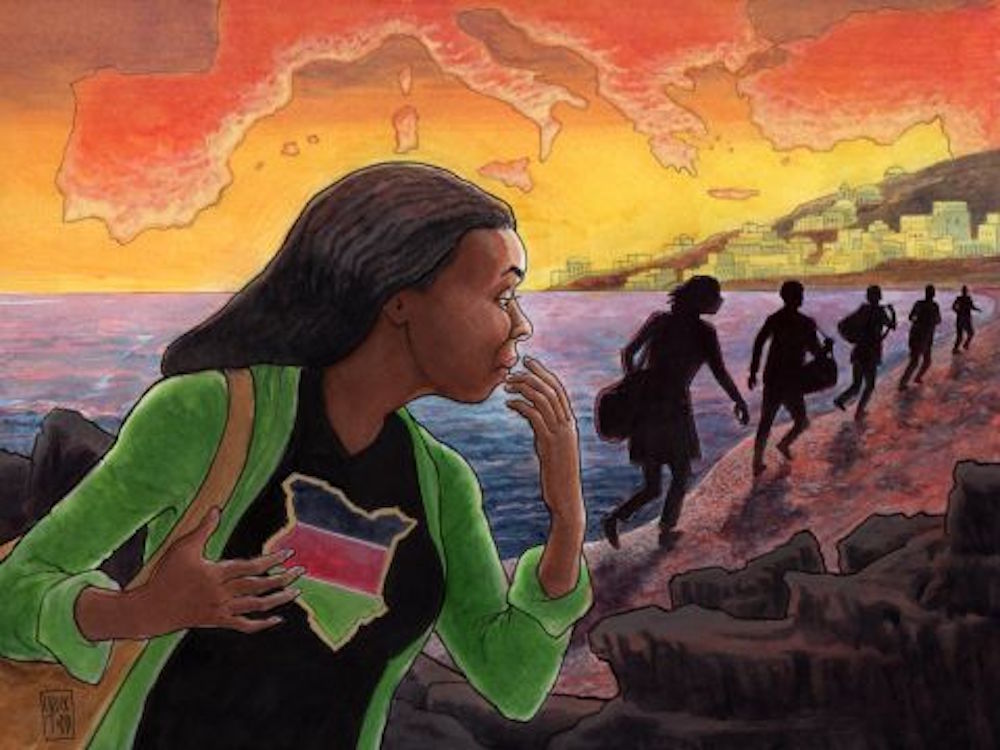

But getting here wasn’t easy. Two of the women flew in on tourist visas, then hid their passports to register as refugees, but the rest used dangerous back routes.

Muthoni, who asked that just her middle name be used to protect her identity, left Kenya six years ago, when she was six months pregnant. She’d been deported from Israel eight months earlier, she says, and she had yet to find a job in Kenya. Just after breaking up with her boyfriend, she discovered she was pregnant.

She already had a daughter who was 6 years old and was being cared for by Muthoni’s mother.

“I felt that by having a second baby out of wedlock, I was exposing my family, especially my mother, to ridicule,” she says. “I wanted to disappear from their lives and have my baby in a faraway country.”

With help from a relative who was a travel agent and human smuggler, and using the savings she’d collected while in Israel, Muthoni traveled to Turkey on a business visa. Once there, her relative connected her to a smuggler in Turkey who promised to organize her transportation to Greece.

“This was the only easy part of the journey, because I traveled by air,” Muthoni says.

In Turkey, Muthoni paid the second smuggler 170,000 shillings ($1,661) for transportation to Greece.

The first leg of that journey was by a cargo van that didn’t have any rear windows. Twenty-three migrants, including four Kenyans, were squeezed together. The van dropped them in Izmir, a port city in Turkey, and the group waited for nightfall before setting out on the 85-kilometer (53-mile) walk to the crossing point.

The crossing point was at Cesme, a coastal town that sits opposite the Greek island of Chios, the migrants’ destination. They walked at night, and hid in shrubs and caves during the day.

“I didn’t tell anyone that I was pregnant, and it didn’t show that much because I’m naturally big,” she says.

Pressure on her pelvis threatened to slow Muthoni down, but she had no choice.

“I had to keep up with the rest,” she says.

On the group’s second night, Turkish police officers saw them and opened fire, scattering them. Muthoni took cover under a shrub, and stayed there until morning. Once there was daylight, Muthoni called out for another Kenyan in the group.

“He answered from the top of a tree, and when I looked up, I saw about six other migrants hiding with him,” she says.

They found a man grazing his goats, and spent the day in his home, she says.

A 2014 report by Amnesty International says that at least 17 people were killed by Turkish border guards’ gunfire between December 2013 and August 2014 near the Turkey-Syria border. In some cases, the report states, there was no warning before guards opened fire.

Muthoni’s group reached the crossing point on the third night. That’s when the worst part of the journey began, she says.

Two smugglers, who had been with the group since Izmir, inflated a rubber boat they had been carrying and asked the migrants to decide who among them would operate the boat.

“We stared at them in shock,” Muthoni says. “All this time, we thought that they would accompany us all the way to Greece. We were now on our own.”

One man from South Sudan volunteered to drive the motorized raft, she says. The smugglers spent about five minutes showing him how to operate it, then they left.

The group boarded the boat and set off toward Greece, but Turkish guards spotted them when they were just a short distance from the Turkish coastline. The guards escorted them back to the shore and told them to disappear, Muthoni says, but they didn’t destroy the boat. The group set out again about three hours later, but once again they were turned back, this time by the Greek coast guard, Muthoni says.

The migrants slept through the next day, hidden in bushes. That night, they crossed over into Greece.

A journey that is estimated by one travel website, Chios Guide, to take about 45 minutes by boat took hours for Muthoni’s group. They relied only on the flickering lights in Chios as a guide.

“Daylight found us in the sea, and the sight of the massive sea made us panic,” she says. “I think smugglers tell people to ride the boats at night because then you can’t see anything and so you have no fear. We were afraid that we’d gotten lost in the sea and the boat would soon run out of fuel. Women started crying.”

The boat reached the shore, and someone immediately poked a hole in it with a stick. The smugglers had instructed them to destroy it soon after they landed, because if the guards found them with the boat intact, they could force them back aboard, tie the boat to their vessel and take them back to Turkey.

“We were not even sure that we had arrived in Greece,” Muthoni says. “We thought that maybe we had landed on a Turkish island. We only believed that we were in Greece when we found an old cement bag with Greek writings on it.”

Smugglers had instructed the migrants to give themselves up to the police as soon as they landed in Greece, on the expectation that authorities would respect Geneva Convention guidelines forbidding deportation to a war zone.

“They told us we would not be deported as long as we said we were from Somalia or any other war-torn country,” Muthoni says.

Tired and worn out, the migrants wished for their own arrests. And Muthoni had other worries: She hadn’t felt her baby kick in at least 12 hours.

“I was worried that she had died,” she says. “I prayed that we got arrested soon so that I could get medical help.”

The group found a home on the island and asked people there to call the police.

Muthoni was taken to a hospital as soon as police arrived. The baby was OK. Muthoni registered as a Somali asylum seeker and was admitted into a shelter in Thessaloniki, the only one with space available, she says.

The rest of the migrants told Muthoni they were held for about two weeks, then released to live in Greece after being fingerprinted and undergoing medical screenings.

Smugglers in Kenya charge between 400,000 shillings ($3,912) and 500,000 shillings ($4,891) to organize these trips, according to migrants in Europe and people in Kenya who have sought their services. Some Kenyans work for years to save the money.

For some, the search for a better life ends in death.

Jane Njoki Kabue, a Kenyan, didn’t survive her journey. Her husband, John Nyaga Kabue, also a Kenyan, says she was on a boat that sank in August 2010, during a journey across the approximately kilometer-wide Evros River separating Greece and Turkey. Migrants consider the route one of the safest ones into the European Union, but the crossing can be dangerous at night.

John Nyaga Kabue moved to Greece in 2008. His wife planned to join him there. But instead of enjoying a reunion, Kabue searched for her for a year before he found her body in a mass grave in Sidiro, a village in northeastern Greece.

In a speech he gave in 2011 when he visited the Evros River, Kabue said DNA testing confirmed that the body found was his wife’s.

Around the time Njoki traveled, 16 migrants, mostly Somalis, drowned trying to cross the river. It’s not clear whether she was on that boat.

The Evros River route was, at one time, a popular entry point into Greece. Grace, a Kenyan who arrived in Greece in 2011 when she was still a teenager, says that boat ride took just a few minutes. Her elder sister, Njeri, had come to Greece a year earlier by sea, but later heard from friends about the Evros River option. Both women asked that their full names not be used to protect their identities.

In October 2010 the UNHCR, quoting Greek sources, said several hundred people crossed the Greece-Turkey land border each day. At that point in the year the agency had recorded 44 people drowning while trying to cross the Evros River in 2010, but they thought the number was higher. It’s not clear how many people entered Europe via the river crossing. News reports have quoted Greek villagers who claimed that there were mass graves in the area containing the bodies of migrants who died trying to cross the river.

In 2012, the Greek government erected a barbwire fence along a stretch of land border to block migrants.

Kabue wanted to exhume his wife’s body to bury her in Kenya but couldn’t afford it.

“Jane was coming to look for a job, just like other Kenyan women you find in Greece, but it was not to be,” Kabue says, fighting back tears.

Written by Wairimu Michengi for Pulitzer Centre as part of the series, In Limbo: Kenya’s Exodus to Europe.